8/2/2021

Today is my second day at Abbaye Saint Marie de Fidelite, a Benedictine convent in Jouques, France, near Aix-en-Provence.

Before describing that experience — which I must say is one of the most peculiar and beautiful of my life — I should wrap up Poland.

Ah, Poland. Can’t say I’ll miss the cabbage/potatoes a lot, but overall, I learned a lot on my trip and would recommend the country as a worthy stop on any European adventure.

My last stop in Krakow was a bit too long, especially after Victoria left and I had another two days waiting for the only flight that week that went to southern France. I could truly draw a map of the city, having walked its streets four or five times over during my week-long stay.

When Victoria left, I had to move to a youth hostel, which was aptly named “Let’s Rock Hostel.” If you follow the blog, you’ll notice that Poles have a penchant for American cliches (the “Cool Club” for instance).

The Let’s Rock Hostel did indeed have rock music blaring, mostly from its karaoke bar downstairs where well-meaning Poles tried their hands at our beloved American classics.

Walking up to the check-in, I was greeted by a psychedelic stairway, with mushrooms and scenes of planets painted up and down the walls. I’m still a bit confused by the theme, but at an $8/night rate, I can’t really complain.

While my final two days were quite lonely, being my first time truly on my own, I used the time to reflect on what I had experienced in Poland.

Like I mentioned last week, Victoria and I got to experience lots of WWII and Cold War history right where it happened. Both the museums and the streets of the cities themselves were a living lesson of the grit and perseverance of the Polish people as they endured calamity after calamity.

My greatest lesson in tragedy, however, was Auschwitz.

Going to Auschwitz and Birkenau was something we simply had to do. It’s an hour from Krakow and extremely accessible by bus. You can’t go to Poland without seeing its most notable — and most devastating— tourist attraction.

The feeling I had on the bus that morning was a dread I can only trivially compare to the feeling I had the morning of my SAT; I knew I had to do it, but I really didn’t want to.

The thing is that until that visit, I could think of the Holocaust as a massive tragedy, the greatest tragedy, but largely as a historical event, boiled down to staggering statistics of death and suffering.

I knew that after seeing the physical location of some of the Holocaust’s worst moments, statistics would melt away into an intimate look at the deep pain and loss that occurred. It would become a living reality.

The other thing that scared me witless was the knowledge that the Holocaust did not happen all that long ago and was not the last genocide to occur in the last two centuries (Rwanda, for one).

One thing I had learned from the exhibits and stories throughout my travels was that no one really thought such horrors would occur, least being the Jewish victims. When I got to Auschwitz, I heard stories about Nazis politely giving women towels and handing people bars of soap as they entered the gas chambers, maintaining their cool as thousands walked to their death daily.

Nobody ever thinks that something that bad can happen to them.

Walking through the bunk rooms (and that’s embellishing — these were more like cattle stalls), hearing the stories of lashings, hangings, rapes, shootings, starvation, and humiliation, I shuddered knowing that truly every form of evil flourished in this place. Greed, blood lust, racism, pride, avarice. These were encouraged and cultivated.

It was sickening and I felt nauseous for the rest of the day.

I apologize for such a depressing tangent, but I think it’s important to remember the suffering more than just a page in your history book. They say “never forget” for a reason; people didn’t think it was possible...but it is and it could be again.

Well now I owe it to my loyal readers to lighten things up a bit. Fast forward to Marseille, France, my next destination after Krakow.

Marseille isn’t necessarily the glamorous destination you think of when you hear Côte d’Azur. It certainly didn’t feel great hearing: “you’re alone...in Marseille!?”

Don’t worry, I’m in the safe sanctuary of the nuns now.

Nevertheless, I actually had quite a bit of fun and a chance to adjust to traveling alone. The night I arrived, I went down to the hostel bar for a glass of French wine (woooow fancy). In a feeble attempt to befriend the locals, I lurked around, waiting for friends to emerge.

(Aside: making friends at hostels is overall easy, but incredibly daunting, especially when you stopped regularly speaking French in high school)

But eventually, a local took pity and started chatting with me. This is when I learned that Marseille, especially on Friday’s after 11 pm, is actually pronounced “Marseille, babayyyy!”

Satisfied with this new knowledge, I went to bed, hyper-focused on not awaking my bunk mates, only to knock over every last piece of luggage in the room.

Ah, hostels.

When you look up “things to do in southern France” you get the classic “go to Nice, go to St. Tropez, visit Cannes!” Well that’s nice if you own a yacht, but as of now I only have a large backpack and a jar of Polish peanut butter (it sucks; please send Teddy’s at your earliest convenience).

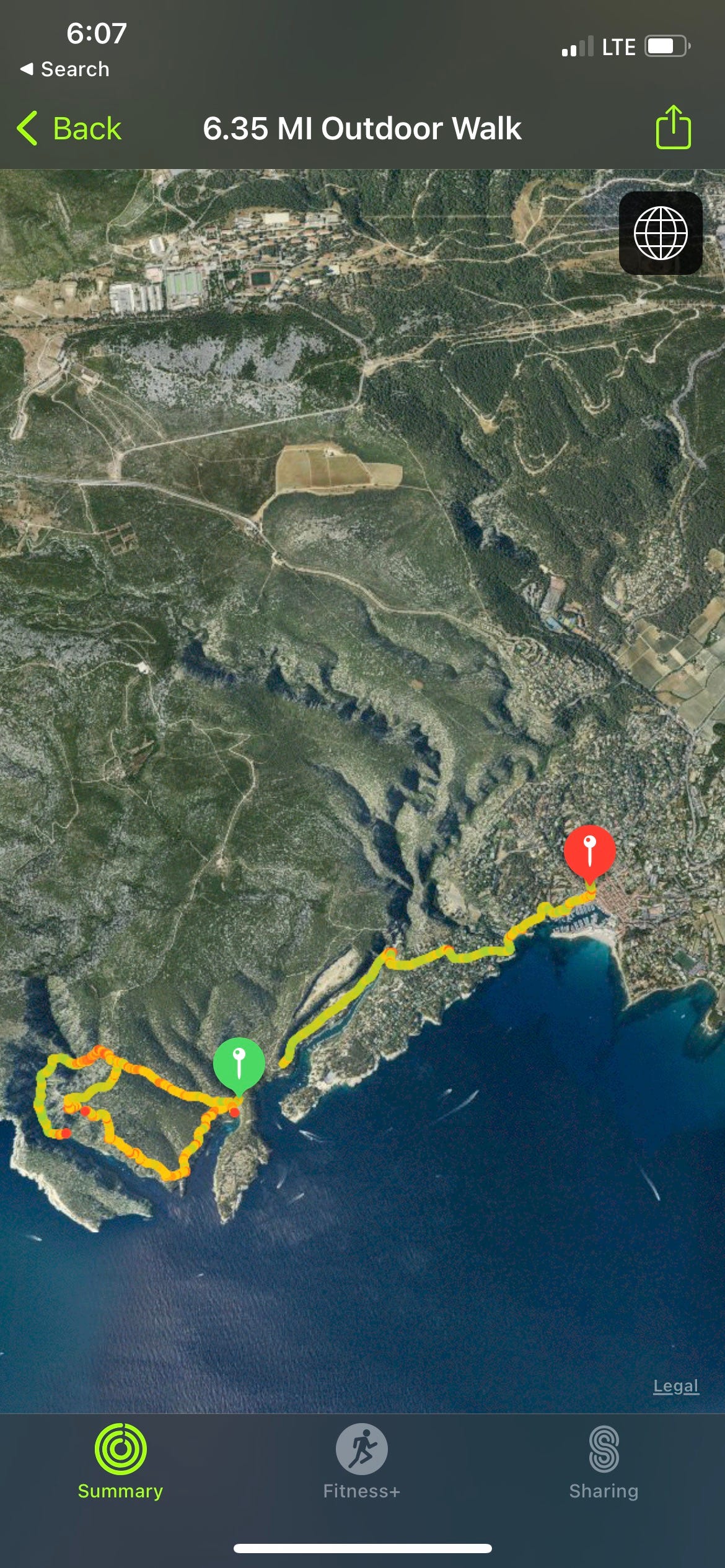

Luckily, between Marseille and Cassis, there are the Calanques, a national park of towering limestone cliffs along the Mediterranean ocean. Carved into the cliffs are narrow, rocky beaches with sparking turquoise water. Hundreds hike to them to spend the day enjoying the warm water.

I ended up doing a ~6 mile loop in the park, truly stunned by the sights of the ocean, cliffs, and iconic beaches hundreds of feet below.

While it wasn’t a crazy trek I did feel really accomplished for having completed my first big outing all alone. Getting to Cassis took two metros, one train, and an Uber all after having missed the direct bus because I didn’t have cash. It’s little inconveniences like these that make me feel incapable and especially lonely. But when I overcome them, as silly as it sounds, I feel able to continue with this fellowship and the uncertainty it brings.

What’s more, I go on these little adventures with the bare minimum. A cheap sandwich, my travel towel, some sunblock (yes mom and Mandy, I wore sunblock), my earbuds, and tons of water. That’s it! None of my fancy hiking equipment or anything like that. If you want to make it happen, it doesn’t take much.

Aaaaanyway, after my hike and a couple of naps on various beaches, I wandered around Cassis, taking in the quaint alleys, cobblestone streets, and stunning coastal views, all the while dribbling ice cream on myself (ze stupeed Americain).

I sat on the train back to Marseille feeling a little lonely, thinking of how much friends and family would have enjoyed this day. But mostly I felt accomplished.

8/4/2021

Pulling up to Abbaye Notre Dame de Fidélité, I was experiencing a mix of emotions. I was probably the most nervous I’ve been the entire trip, fully unaware of what kind of environment I was walking into. Would I be the only layperson there? Do people even visit nuns?

My fears immediately melted away as I met Christine, a fellow visitor who was kind enough to pick me up from the bus station in the tiny town of Jouques. As I piled all my things into her little French car, she shared that she visits the Abbey each year “pour fair des retraites.” Turns out that lots of French Catholics (and even non-Catholics) visit these historical Abbeys for family retreats or personal reflection time.

The Notre Dame de Fidélité sits on a hill overlooking Provence’s stunning summer landscape: rolling rills, lavender fields, and orchards dot the landscape between the miles and miles of fields and rivers.

As we pulled up, there were French boy scouts (pronounced “scoots” in French) marching around, singing and helping the sisters with their farm work. Visitors milled around an outdoor table, laying down bottles of wine and dishes of beef, fresh tomatoes, and French bread. A nun by the name of Soeur Marie Liesse happily rushed up to me, sweeping me off on a tour of the hotel.

It was every bit as romantically provincial as I could have imagined. It was a movie.

The hotel is an old house apart from the Abbey, where most of the sisters live a cloistered life. Both buildings are stucco with red-tile roofs. Benedictine sisters, like those at NDF, are called to take in visitors per Saint Benedict’s teachings:

“All guests who present themselves are to be welcomed as Christ, for he himself will say: I was a stranger and you welcomed me (Matt 25:35).”

And take care of me they did. I went to be spiritually nourished but mostly I was, well, nourished. My preconception of what an Abbey would be like was colored with a sense of austerity, but this was a place of abundance; incredible food, wine, and company. And lots of joy; everyone was always smiling and friendly.

Let me describe my first meal in vivid detail (trying to distract my hostel hunger as I eat out of a jar of peanut butter):

After a long day of traveling to Jouques, I sit down to a table with rosé, made by the nuns from their vineyards, and freshly-baked French bread. Everyone pitches in at the Abbey, so after sampling these, I got up to bring out platters of a carrot salad dressed in French mustard. Seeing as it was lunch, I figured this was it. But no. Next came the most succulent stewed beef I’ve ever had, seasoned with what I can only guess was herbs du Provence. It was accompanied by baked tomatoes, grown in the sisters’ very own garden.

I got up after this absolute feast to bring all the plates to the kitchen. When I came back, to my surprise, there was a hefty piece of chocolate tart on a dessert plate for me. And of course, the sisters brought out a platter of coffee and candies.

^ me

So much for austere contemplation.

But you know what!? After weeks in hostels, I think I’ve earned it.

The best part about these meals was the company. Visitors from all over France were always keen to spark up a conversation, patiently listening to my rusty French.

One of my most interesting encounters was with a priest from Rwanda (I’ll omit his name to respect to his privacy). Father X studies in Rome but was on vacation in southern France, helping staff shorthanded parishes.

I asked him about his calling to be a priest over a shared breakfast on a sunny morning. He calmly told me that his family had been torn apart by the Rwandan genocide when his mother and his older siblings were killed for being Tutsis.

After the genocide, at only seven years old, he had already experienced more trauma than most adults see throughout their lives. His troubles continued, however, when his father went on to marry a Hutu woman, bringing scrutiny and hatred upon his family.

The priest grew up struggling to understand his father’s decision, even resenting it, especially when it meant him losing government tuition aid for Tutsis who, pre-genocide, were excluded from most higher education opportunities, according to Father X. He couldn’t get this help because his father was a “traitor” for marrying a Hutu woman.

This mounting frustration led him to confront his father, asking him why he would marry a Hutu. Turns out, his father did so to provide for his family, knowing that surviving Tutsi women were still emotionally healing from the genocide. It would be difficult for them to care for themselves, let alone a family. Father X started to see that his father had made a difficult decision — one that surely weighed on him —in order to ensure that his young children were well-fed, educated, and raised properly.

Father X also came to realize that his stepmother had suffered in her choice to marry a Tutsi; her family was deeply disapproving. He confronted her, wondering why she would marry a Tutsi. She shared that she had had a calling to take care of orphans since her teenage years and wanted to be a good mother to Father X and his little brothers.

“I started calling her mama from that day on.” Father X’s face lit up as he spoke of her kindness and self-sacrifice. “She loves me and my brothers as her own children and I love her as my mother.”

Understanding the selflessness of both his parents, Father X started to consider the priesthood to, in his words, “minister to all people, to be more open.”

There were also little signs along the way, he shared. “I never had to pay my tuition.” Without aid, Father X would not have been able to continue attending university. Yet, by what he believes is the grace of God, he was never charged for his remaining semesters of study.

“I saw God’s hand in all of this.”

I never really expected to see a parallel between Poland and Jouques. But one theme remains: do not forget tragedy, and more than that, turn it into good.

In Poland, I walked through rebuilt cities and witnessed the national strength and faith of a people forged by the legacy of warfare. In Father X’s story, I learn about the goodness that can be born of tragedy; a desire to help others because of the sacrifices that have been made for you in the toughest of times.

P.S.

These nuns are (sorry sisters) total badasses. They run their own vineyards, olive/apricot orchards, and lavender fields. You routinely see them driving around in tractors and trucks to complete their different chores and tasks for the day.

And the wine was *chef’s kiss*.

P.S.S.

I just want to acknowledge the kindness that has come my way especially when I’ve been feeling my loneliest. Every single family visiting Jouques offered to host me in their homes throughout France, even if we only talked for a few minutes. I left with addresses and phone numbers from over five people. Sister Marie Liesse also tried to find a place for me to stay in Lyon so I wouldn’t have to go to another hostel.

As a woman traveling alone, I tend to always prepare for the worse. But there’s lots of goodness in the world too.

I feel as if I'm there with you, Carine!

Top top toooppppp